Introducing Cape Verde

Most people only know Cape Verde through the haunting mornos (mournful songs) of Cesária Évora. To visit her homeland – a series of unlikely volcanic islands some 500km off the coast of Senegal – is to understand the strange, bittersweet amalgam of West African rhythms and mournful Portuguese melodies that shape her music.

It’s not just open ocean that separates Cape Verde from the rest of West Africa. Cool currents, for example, keep temperatures moderate, and a stable political and economic system help support West Africa’s highest standard of living. The population, who represent varying degrees of African and Portuguese heritage, will seem exuberantly warm if you fly in straight from, say, Britain, but refreshingly low-key if you arrive from Lagos or Dakar.

Yet life has never been easy here. For centuries, isolation and cyclical drought have resulted in famine. Generations of Cape Verdeans have been forced to emigrate, leaving those at home wracked by sodade – the deep longing that fills Cesária Évora’s music. While hunger is no longer a threat, you need only glance at the terraced hillsides baking in the sun to understand that every bean, every grain of corn, is precious.

Though tiny in area, the islands contain a remarkable profusion of landscapes, from Maio’s barren flats to the verdant valleys of Santo Antão. And Fogo, a single volcanic peak whose slopes are streaked with rivers of frozen lava. The beaches of Sal and Boa Vista increasingly attract package-tour crowds, but Cape Verde remains a destination for the connoisseur – the intrepid hiker, the die-hard windsurfer, the deep-sea angler, the morno devotee

Cape Verde has less fauna than just about anywhere in Africa. Birdlife is a little richer (around 75 species), and includes a good number of endemics (38 species). The frigate bird and the extremely rare razo lark are much sought after by twitchers. The grey-headed kingfisher is more common though with its strident call.

Divers can see a good range of fish, including tropical species such as parrot fish and angelfish, groupers, barracudas, moray eels and, with luck, manta rays, sharks (including the nurse, tiger and lemon) and marine turtles. Five species of turtles visit the islands on their way across the Atlantic. Nesting takes place throughout the year, but in particular from May to October.

Remote Life: The Rabalodos of Cape Verde

© 2017 Pete Martin

Cape Verde has ten islands in all, nine of which are populated, and each with very different characteristics. I could easily island hop; Fogo with its volcano and wine is next door, but regrettably I have arrived too late for major plans but at least I have a guide for Santiago Island.

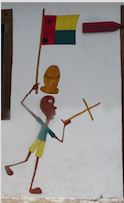

After the wonderful market of Assamada, we continue to the east coast of the island. On a hillside above the ocean lives a small isolated community called the Rabalados. The tribe do not invite visitors but if any arrive they are welcomed. A young, thin woman holds her baby

on her hip (not on her back as is usual across Africa) and directs me into a bland concrete building. Inside is a display of their arts and crafts. One wall has numerous pictures drawn by the woman. Most contain simple sketches of stick people with fish tails for legs. I give her an

encouraging acknowledgment of her artistic skills and in return she makes it clear to my guide, in Creole, that that we are free to wander around the small village.

It’s not much of a welcome and I have no information about these people. It seems the tribe is isolated by choice, deciding to live away from the nearby town in neat rows of straw huts. The two huts at each end are for communal cooking and behind the huts are the sties for their pigs.

Dogs and goats wander aimlessly as we do. There are no men here, all either fishing or working the nearby fields. The young women (and one old one) and a few boys sit holding babies on the floor with their backs against a wall remaining in the shade. None look happy.

I have so many questions. Such as where do they have their children, here or in a local hospital? How do they meet their partners when it’s such a small community? Where do they buy their livestock from if they don’t interact? But there are no answers today.

My guide feels fine strolling around but I feel intrusive. When I say that we should go he suggests that I should leave some money. As the young woman who welcomed us in is now breast feeding, I offer it to the old women. She swats the money away and insists I give it to the young

one. It’s a bewildering tribe.

On the way out, a young boy is playing joyfully with two sticks and an old tire. A man with a long wooden fishing rod and a bag full of fish is returning to camp too. He looks proud and joyful. Both are in total contrast to the miserable, bored females.

Pete Martin is a traveller, author, journalist and coach. This is an adapted extract from his latest book “Fantafrica”. Soul searching for his true calling, the one activity to give himself up to that will replace ‘work’, he is invited to a volunteering project – developing a football academy

in Ghana. Whilst in Africa, Pete spent some time in Cape Verde. In other adventures, Pete has circumnavigated the world, which included the Trans-Siberian Railway across Russia and Amtrak across the USA. More details of his books can be found at www.petemartin.org.